On Tuesday, May 10, 2022, the School of Public Health held an event to share and discuss findings on indicators of health and sustainability for Baltimore, Maryland, which was among 25 cities studied in a new ‘Urban Design, Transport and Health” series, published in The Lancet Global Health. The report on spatial indicators, including walkability and public open space access, was co-authored by Kinesiology Associate Professor Jennifer D. Roberts who also organized the event to spur dialogue about solutions with Drs. Amy Sapkota, Rianna Murray, and Megan Latshaw.

The new Lancet Global Health series assesses city planning policies and the urban design and transport features of cites across Australasia, Asia, Europe, USA (cities included Baltimore, Phoenix and Seattle), Central and South America and Africa, with the aim to inform policy directions for more healthy and sustainable cities worldwide.

The team of more than 80 researchers in 25 cities across 19 countries used standardized methods to assess the policy settings and lived experience of city-dwellers. They identified thresholds for urban design and transport features that would increase physical activity by way of active transport and ultimately promote health. Also, theyused spatial indicators to assess the health-supporting nature and sustainability of each city and identify inequities in access.

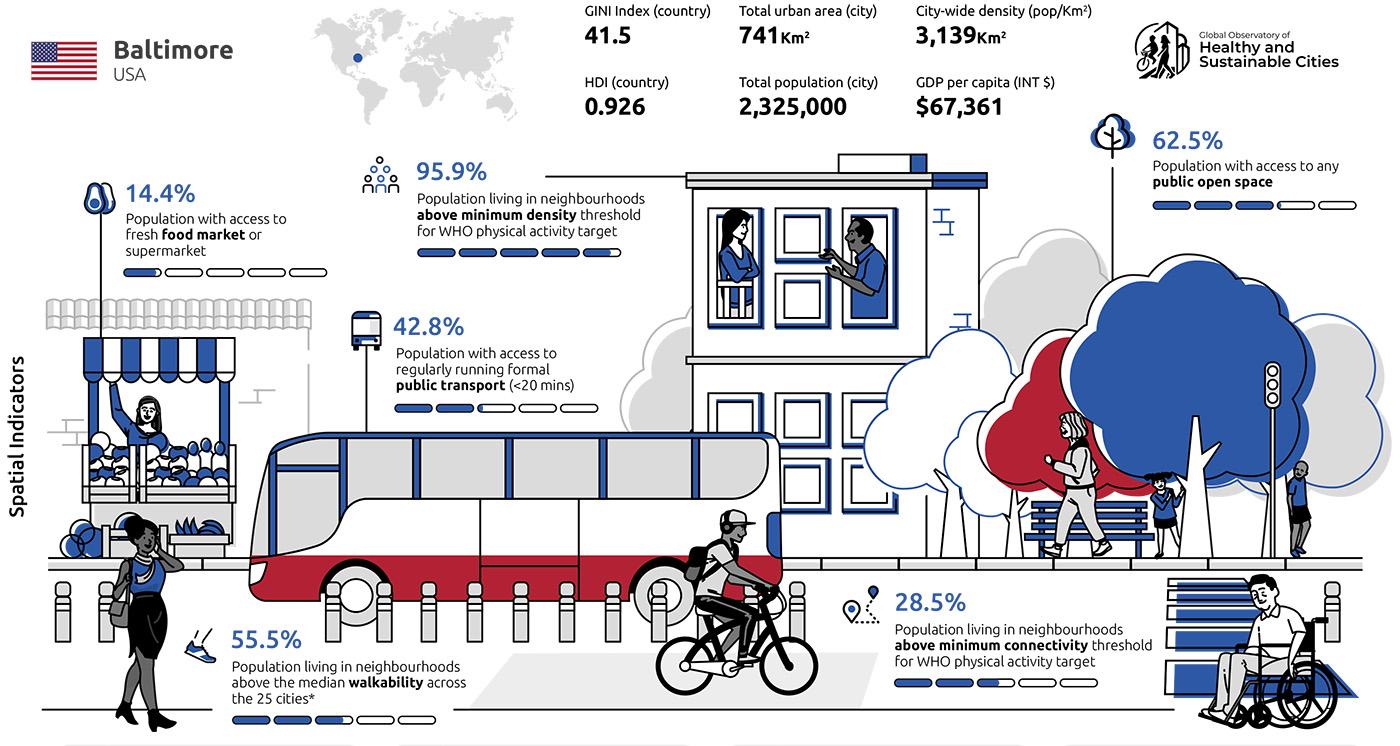

At the SPH event, Dr. Roberts presented the findings about Baltimore, which ranks below average on most indicators of health and sustainability compared to the other cities in the study.

Among the key findings:

- the majority of neighborhoods in Baltimore have low walkability relative to the 25 cities in this international study

- a minority of residents have access to public transit stops near their homes

- only 40% of Baltimore residents have access to public open green space

- Approximately 14% of Baltimore residents have access to a fresh food market or supermarket

The percentage of Baltimore's population with access within 500m to a food market, convenience store, any public open space or a larger open space and public transport is well below average compared with other cities studied.

“There were no big surprises,” said Dr. Roberts of the report. “There is a lot of room for improvement in terms of making Baltimore a healthier and more sustainable city, such as expanding access to fresh fruits and vegetables, safe and high quality open space, walkable areas and public transport. There is also room for improvement in terms of dealing with the inequities of these issues that largely fall along income and racial lines.”

After Dr. Roberts presented the findings and shared a video with comments from Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott, a panel of experts in urban planning, health disparities and environmental health discussed their reactions and the implications for taking action in Baltimore.

“It is an indictment on what a terrible situation Baltimore is in,” said Seema Iyer, director of the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance-Jacob France Institute at the University of Baltimore of the report. “We need to take a stand because nothing is going to change if we don’t act with urgency.”

Dr. Amir Sapkota, professor of applied environmental health, who co-authored the Maryland Climate and Health Profile Report (2016) shared insights about poor health outcomes in Baltimore compared to other parts of the state.

“Baltimore fares worse than other counties in the state in asthma hospitalization, extreme heat and heart attacks,” he said. “If it was a difference of majority Black vs majority White populations, Prince George’s County would fare poorly as well, but it is above average for the state for these indicators.”

Yet the panelists ultimately focused on solutions and taking action to improve access to fresh food, open space and opportunities for physical activity in Baltimore.

Robbyn Lewis, a Maryland State Delegate from District 46 (Baltimore City) with a public health background, shared opportunities for policy change.

“Baltimore is in big trouble if we don’t do something (you heard others say),” she said. “But in public health we are optimists, we can attend to those realities and still believe that something better is possible.”

She described efforts to bring people together in her neighborhood through the creation of the Liveable Streets Coalition, which is focused on addressing obstacles to neighborhood walkability and increasing pedestrian safety. She also talked about her efforts to improve transit through better bus availability and to increase green space in neighborhoods.

The panelists convened by Dr. Roberts because of their diverse expertise and collective commitment to improving health and well-being in Baltimore agreed that the data must be used to inform action and create policies that will impact changes in Baltimore.

“I am excited and hopeful that the connections we made will continue and that students could be pulled into internships and other opportunities,” said Dr. Roberts. “Our conversation was realistic - there were no rose colored glasses – but it had an energy of let’s get to work and improve Charm City. It was hopeful.”