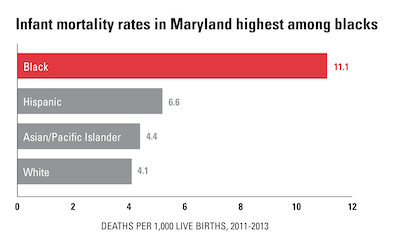

Infant mortality rates in Maryland are highest for African American and rural infants, and researchers at the University of Maryland School of Public Health are helping the state determine why.

Faculty from the Department of Family Science and the Maryland Center for Health Equity are embarking on a year-long study for the Maryland Health Care Commission analyzing risk factors for infant mortality, examining the use of community health workers and pregnancy navigators and cataloging what innovative health programs already exist.

The 17-member team, which includes faculty, doctoral students and undergraduates, will present preliminary analyses next month and submit the initial report to the state in November.

“In many ways this is a golden opportunity to take on a persistent and tragic problem, bring various faculty and students into the project and hopefully make a difference when it comes to policy in Maryland,” said Sandra Quinn, chair of the Department of Family Science, who is leading the study.

Investigators include Marian Moser Jones and Edmond Shenassa, both associate professors of family science; Marie Thoma, an assistant professor of family science; and Elaine Anderson, professor of family science. Faculty research associates include Amelia Jamison and Devlon Jackson. Associate Dean for Research and Principal Associate Dean Dushanka Kleinman will serve as a consultant.

The Maryland General Assembly passed a bill last April mandating that the Maryland Health Care Commission produce the study, which will be the first state analysis of infant mortality since 2011. Evidence suggests that mortality rates among rural infants have increased in recent years, while rates among blacks have remained high.

The U.S. has the highest infant mortality rate in the developed world, and the death rate is around three times higher for both black women and their babies than white women and theirs. In Maryland, the highest rates can be found in heavily black areas like Baltimore City and rural counties like Somerset and Worcester.

Disparities based on race, geography and other factors persist across maternal and child health issues, and faculty across the school are working to understand why.

Undergraduate students in Assistant Professor Marie Thoma’s FMSC 310: Maternal, Child and Family Health course last fall examined inequalities in prenatal care, breastfeeding and other issues related to maternal and child health. As groups, they dug into epidemiological data to identify needs in Maryland, produced data briefs and used their findings to develop public health communications plans.

Though such analysis is an essential component of working in the maternal and child health field, undergraduates rarely get a chance to develop their data fluency. Thoma said some of the groups’ findings were so helpful she incorporated them into her lectures on the topics.

The project received an Innovative Teaching Award from the Association of Teachers of Maternal and Child Health, which is funding undergraduate and graduate teaching assistants.

It was in that class that Thoma recruited Marie Ngobo Ekamby, a junior public health science major, to work on the state infant mortality study.

As part of the larger state study, Ekamby, Thoma, Jackson and others are now developing the inventory of Maryland programs combating infant mortality. The process involves collecting data on each program, interviewing program directors about their work and conducting an online survey to gather further details.

For Ekamby, the project was a chance to examine how maternal and infant mortality affects African Americans.

“I wanted to learn more about maternal mortality and what pregnancy outcomes look like for women who look like me,” Ekamby said.

Other students involved in the project include graduate students Jessica Gleason, Dane De Silva, Lisa Tolchin and Debbie Shelaf and undergraduate students Anne-Olive Nono, Arrey-Takor Ayuk-Arrey, Nava Katz and Afua Nyame-Mireku.

Quinn reflected on the study, its inclusion of students as part of the research team, and the impact.

"We are all committed and passionate about bringing our faculty and students together to reduce this tragic problem," she said.