This story was published in EnTERPrise, the University of Maryland's annual research magazine, showcasing cutting-edge and high-interest scholarship and discoveries that address the grand challenges of our time. It was written by Liam Farrell.

Bordering a major East Coast port and braided with highways, Baltimore’s southern edge is a rushing two-way conduit for products constantly flowing in and the detritus of modern life continually flushing out. Much of this effluent is headed for the neighborhood of Curtis Bay, home to a trifecta of foul final destinations: a landfill, a medical waste facility and an animal rendering plant.

When Destiny Watford was growing up there more than a decade ago, adults urged her to get out as soon as possible. Brick rowhomes, churches, corner stores and school playgrounds share the air with a coal silo and fleets of diesel trucks, and Watford saw neighbors die of lung cancer and her mother struggle with asthma attacks. The community already had some of the nation’s most polluted and deadly air, according to a collection of studies, when plans were announced in 2012 for a new trash incinerator—permitted to burn 4,000 tons a day and spew up to 1,240 pounds of lead and mercury annually—less than a mile from her high school. Anger overcoming her shy nature, then-16- year-old Watford co-founded an activist group and looked for allies in what became a four-year quest to stop it.

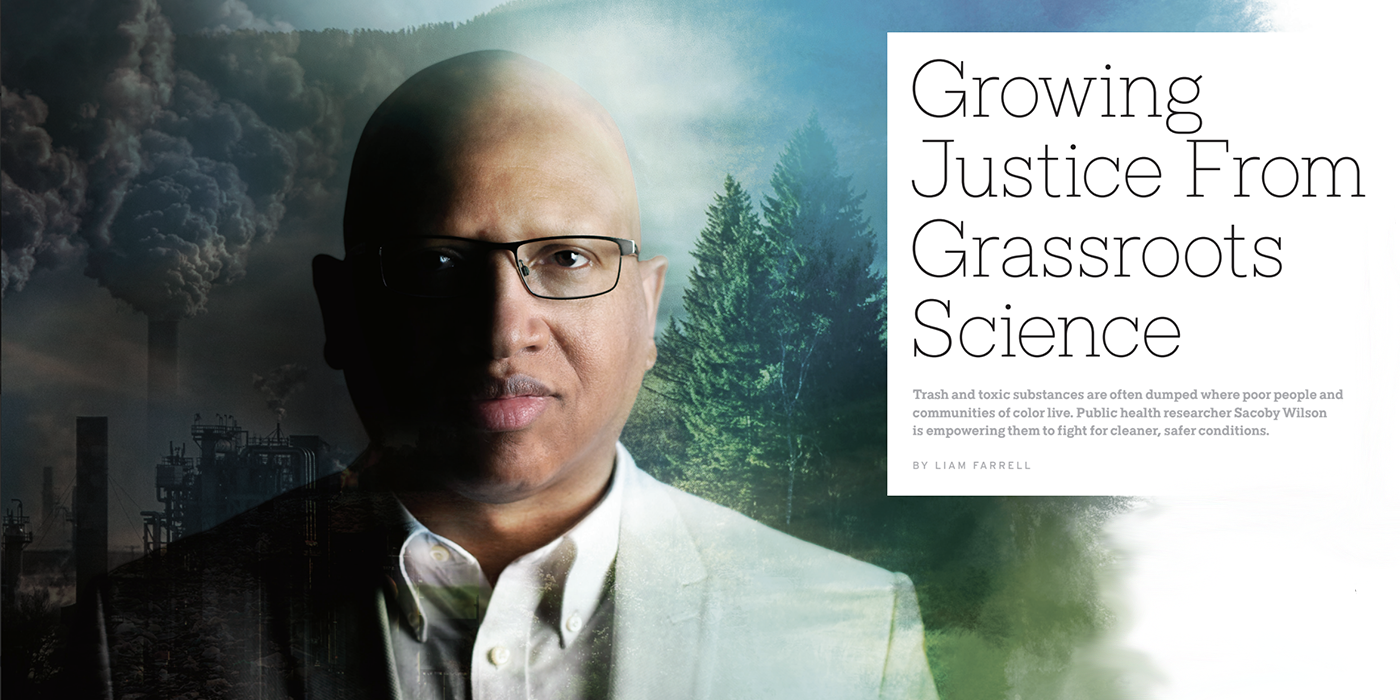

One important guide would be Sacoby Wilson, an assistant professor in the University of Maryland’s School of Public Health. An expert on environmental toxins and the sociopolitical structures that make them so abundant where people of color live, Wilson helped the teenagers make contacts with legal and environmental groups and get their hands on the data they needed to mount a challenge to an interna- tional corporation.

“We weren’t lawyers or experts in any way, shape or form,” Watford says. “Sacoby ended up being one of those folks. He was really influential in making sure we had those connections.”

Now an associate professor with the Maryland Institute for Applied Environmental Health and Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Wilson is at the forefront of investigating how the places where people live can determine their health. A proponent of community- based participatory research, he trains and assists people in getting the information they need to protect their families and homes. Wilson and his Center for Community Engagement, Environmental Justice and Health (CEEJH) have worked alongside overburdened and under- served people of color and low-wealth populations from Houston and New Orleans to Washington, D.C., aiming for the nexus of pollution, zoning and community development practices that disproportionately hurt vulnerable neighborhoods and reflect the ingrained biases of government and private industry actors.

By teaching people how to take water samples, read air monitor data from their homes and understand complex legal and regulatory structures, Wilson tries to do more than just document what happens to someone who lives near or works in a power plant or hog farm. Ultimately, as climate change intensifies and new threats like COVID-19 show how deadly historic health disparities can be, Wilson wants to help people “liberate themselves from the toxic trauma they are experiencing every day.” “In working with people, you got to provide services,” he says.

“(It’s) about solutions, about action, about mitigation, about investments.”