As the omicron variant circulates more widely, UMD School of Public Health experts advise that we need a multi-layered approach to best minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission.

In their perspective article “Applying the Hierarchy of Controls: What Occupational Safety Can Teach us About Safely Navigating the Next Phase of the Global COVID-19 Pandemic,” Neil Sehgal and Don Milton present a new model for understanding different COVID-19 prevention measures that updates the “swiss cheese” model of pandemic defense to one that elevates certain approaches over others.

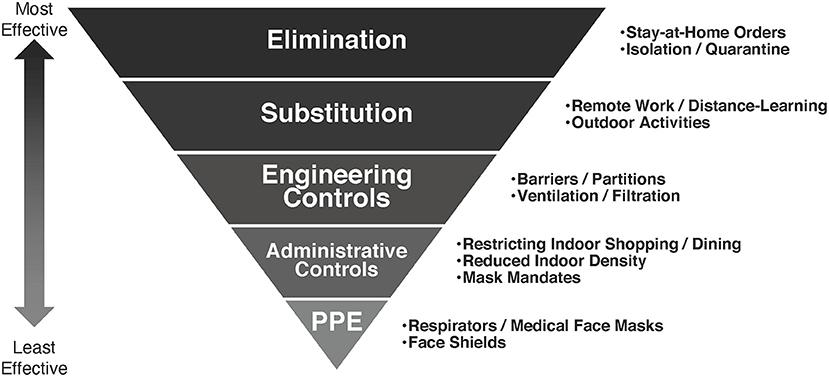

The model is an inverted pyramid that moves top to bottom from most effective to least effective. At the top are elimination controls, which include stay-at-home orders, isolation and quarantine, and vaccines. Then there are substitution strategies, like remote work and distance learning. Next is engineering controls, like partitions and air filtration systems. Last are administrative controls (dining restrictions and mask mandates) and PPE (medical masks and face shields).

The idea is to show that all of these measures are necessary to prevent the spread of COVID-19—but not all controls are created equally.

“It's not to say that masks are not effective or PPE is not effective, but that is to say if you are waiting until that last step to try to prevent a hazard, you're probably waiting too long,” Sehgal said.

The swiss cheese model of COVID-19 interventions recognizes that no method of prevention is perfect. They all have holes (like swiss cheese), and we should layer the controls to fill in the gaps.

“I think one of the challenges of that model is that it doesn’t really adequately address that some protections are better than others,” said Sehgal. “It's not like masks and vaccines are substitutes for each other—they're really complements—and vaccines in the long run are more effective than masks are.”

The hierarchy of controls model is based on research from the occupational safety field.

“If somebody's in a dangerous workplace, and you can eliminate the danger, you should do that,. because it keeps them safer,” Sehgal said. “Or, if there's a safer activity, as opposed to a more dangerous activity, you should substitute that safer activity. You can also do things like use tools and tech, engineering controls to try to make the workplace safer.”

Deciding which controls to implement is more important than ever, Sehgal says.

“I'm not terribly comfortable with this realization, but I think it's the likely set of circumstances going forward: I think COVID will be with us for the foreseeable future,” he said. “As a result, we can’t wait for things to get significantly better than they are now, which means we have to take reasonable and additional precautions. For me, what that means is we're going to have to make decisions about what precautions we put in place.”

Sehgal says some of those precautions should include more investment in UV air cleaning systems, which rank higher on the pyramid than masks and could also make flu seasons significantly easier.

“That engineering control is more effective than asking everyone to wear the right mask perfectly every time, which means we should try to do that more often,” he said.

Part of the problem in how we’ve been trying to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 is that we’re overly reliant on individual actions, Sehgal says.

“If you are relying on people to do the right thing every time, even well-intentioned people will slip up,” he said. “Any process that relies on perfect human performance, that process is doomed to fail.”

Another problem is that people unlikely to take the most effective precautions are unlikely to take any precaution. That is, people unwilling to get vaccinated are probably also unlikely to wear masks. But there’s a solution, Sehgal says: mandates.

“When you have the ability to require people to do things to protect the people around them, those things end up happening,” he said.

He’s hopeful that policymakers—maybe even Joe Biden—will read the perspective article.

“The people I want to see and understand are policy people, because I think we can make better policy to help us navigate the pandemic,” he said. “We want to help explain to the public that there are several strategies to try to mitigate COVID-19 transmission, and all of them are necessary. None are necessarily sufficient, and some are of relative different effectiveness.”