Adults who were better informed during the COVID-19 pandemic may have been less stressed and better able to manage the uncertainties and changes, but more knowledge may not have had the same impact on children.

Researchers from the University of Maryland (UMD) School of Public Health collected data in Spring 2020 through surveys of 4,249 children, ages 9 to 13, representing 42 countries and eight regions. They examined children’s levels of knowledge and concern and the relation between them. Their study results are published in the journal Health Psychology Research.

“This study highlights the importance of knowing one’s audience,” said Dina Borzekowski, research professor in the Department of Behavioral and Community Health (BCH), director of the UMD School of Public Health’s Global Health Initiative and the study’s lead author. “Especially in a public health crisis, it is important to know that children are watching. Their needs must be met, and this should be considered when producing different media.”

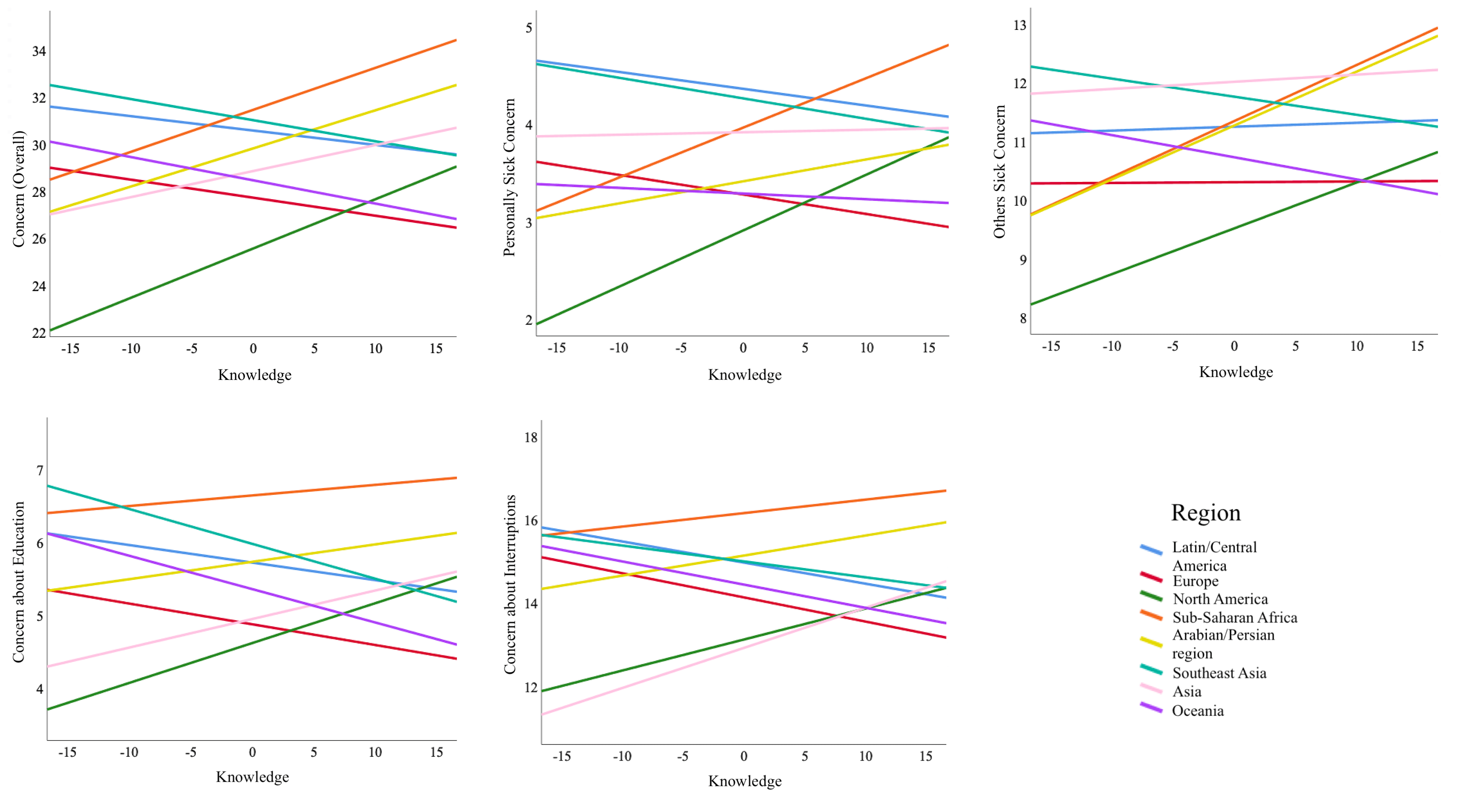

Children from Sub-Saharan Africa, the Arabian/Persian region and North America who were surveyed who had greater knowledge about COVID-19 also indicated a higher greater concern. The researchers created a composite score for concern that was based on how worried children felt about getting sick, others getting sick, not attending school, and missing out on regular activities.

In contrast, children from Southeast Asia, Latin/Central America, and Europe with more knowledge indicated that they had less concern. The findings for children in Asia were less clear, with increased knowledge being associated with greater concern in some but not all areas.

While fewer children got seriously ill with COVID-19 compared to those in older age groups, children around the world experienced and were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in profound ways.

Children, like their parents, watched and heard stories about the ravages of the virus. They sought information and had to wade through myths and unreliable data. Children worried about personal health, the health of loved ones that they were unable to see for extended periods and missing out on the many experiences of childhood. Schools closed, and over 1.5 billion children around the globe were no longer attending classes.

During a public health crisis, children are particularly vulnerable and often overlooked. Concepts discussed during pandemics, such as R Naught and exponential curves, can be difficult for people of any age to understand. News and social media can be alarmists, and young people may worry about getting sick, missing events and being out of school.

“We found that more knowledge was associated with different reactions among children from various parts of the world, suggesting a complicated situation between the message and receiver,” said study co-author Christopher Lane, an MPH candidate at George Washington University. “Crisis communication and its impact on children needs to be studied and improved.”

The researchers offer insights into best practices for message production, especially for children and other vulnerable groups, urging that it is critical to inform without creating concern that may be unduly stressful or harmful to them given their developmental age.

This study, entitled “The Relation between Knowledge and Concern: A Global Study of Children and COVID-19,” is published in Health Psychology Research.